Preference Leakage: Contamination in LLM as a Judge

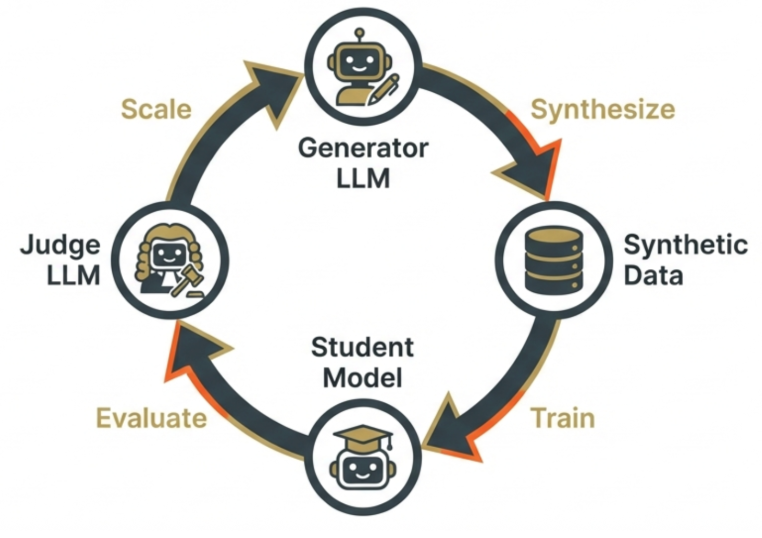

Modern development relies on two pillars of efficiency and scalability: Synthetic Data Generation and Automated Evaluations as shown in the the pipeline which is now the industry standard for aligning and benchmarking models.

Recently I explored a critical vulnerability in the modern LLM development pipeline. As we increasingly rely on Large Language Models (LLMs) to act as both data generators and evaluators (“LLM-as-a-judge”), there is a subtle form of contamination known as Preference Leakage as introduced in the paper. This post summarizes the key technical findings from the paper, explaining how this leakage occurs, its impact on model evaluation, and how we can mitigate it in our workflows.

For the full details, please read the paper.

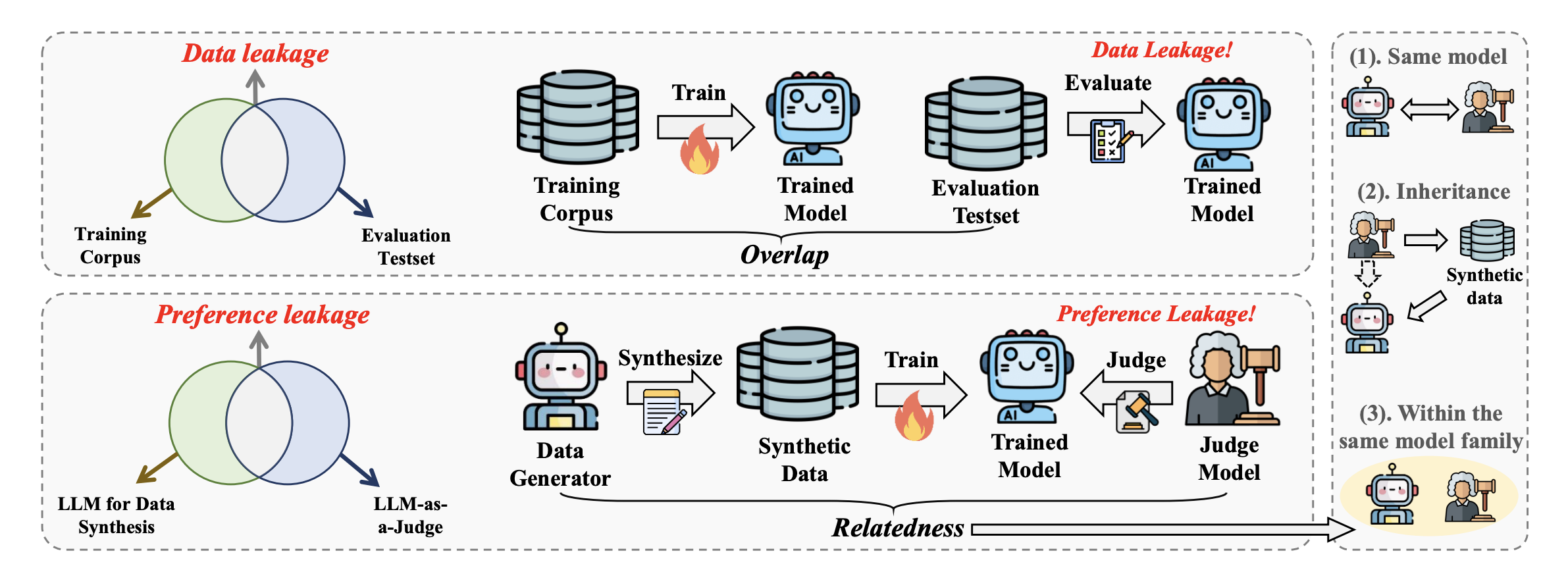

The New Contamination: Preference Leakage vs. Data Leakage

Engineers are likely familiar with Data Leakage, where training data inadvertently overlaps with evaluation test sets, inflating performance metrics. However, the current industry standard—using LLMs as “Oracles” to synthesize training data and then using LLMs again to judge performance—has created a new circular dependency.

Preference Leakage occurs when the Judge LLM has a close relationship with the Generator LLM (the model that created the synthetic training data). Because the Student Model learns the specific preferences (style, format, wording) of the Generator, the related Judge inevitably favors the Student’s output—not because it is better, but because it is familiar.

This “relatedness” generally falls into three categories:

- Same Model: The Generator and Judge are the exact same instance.

- Inheritance: The Judge is the base model for the generator (or vice-versa).

- Same Family: Models share architecture or pre-training data (e.g., GPT-3.5 and GPT-4).

Experimental Setup and The “PLS” Metric

To quantify this phenomenon, the research introduced the Preference Leakage Score (PLS). A large positive PLS indicates that a judge systematically favors a student model trained on data generated by that judge (or its relative) over a student trained on unrelated data. The experiment utilized three major model families (GPT-4o, Gemini-1.5, LLaMA-3.3) acting as generators/judges, and fine-tuned smaller student models (Mistral-7B, Qwen-2.5) on synthetic datasets derived from Ultrafeedback.

Key Findings

Bias is Systematic and Significant

The evaluation on benchmarks like Arena-Hard and AlpacaEval 2.0 confirmed that preference leakage exists across almost all model pairs. Notably, smaller student models tend to trigger higher bias from Judge LLMs. The hypothesis is that smaller models may latch onto superficial stylistic features (which the judge prefers) more heavily than larger models do.

The “Danger Zone”: Subjective Tasks

Not all tasks are equally susceptible. The data shows a clear correlation between task subjectivity and leakage severity.

- Low Risk: Objective tasks like Mathematics, where there is a definitive correct answer.

- High Risk: Subjective tasks like Programming, Writing, and Fairness evaluations. In these “danger zones,” the judge’s stylistic preferences dominate the evaluation criteria.

No Safe Threshold for Synthetic Data

A data mixing analysis revealed that leakage is directly proportional to the amount of synthetic data used. There is no “safe threshold”; even small amounts of synthetic data mixed with human-written data can skew evaluation results.

The Impact of Training Methods

The method used to train the student model significantly impacts the severity of the leakage:

- SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning): Highest leakage (Avg PLS ~23.6%). The model heavily memorizes the generator’s style.

- DPO (Direct Preference Optimization): Significantly reduces leakage (Avg PLS ~5.2%).

- ICL (In-Context Learning): Lowest leakage.

The Mechanism: Implicit vs. Explicit Recognition A fascinating discovery from the research is that Judge LLMs are not explicitly recognizing their “own” students. When prompted to identify if a response came from their student model, the judges performed no better than random guessing. However, they still consistently rated those responses higher. This suggests the bias is implicit—the judge is responding to subtle feature distributions and stylistic patterns rather than “knowing” the source.

Takeaways

As we integrate LLMs into our workflows, we must be vigilant regarding this bias.

- Be Cautious with Synthetic Ground Truth: When generating synthetic data for evaluation or training, assume that using the same model family for validation will inflate your success metrics.

- Evaluate the Evaluator: For tasks without definitive answers (open-ended generation), calculate the Preference Leakage bias before trusting the score.

- Choose Judges Wisely:

- Opt for independent models (e.g., if you train with LLaMA, judge with GPT-4).

- Larger judges generally provide more stable evaluations than smaller ones.